Dome of the Reichstag they call me here in Berlin (and throughout the rest of the world, too), for only a select few know that my name is really Clara. Dome of the Reichstag isn’t wrong, of course – for that is indeed my profession.

They say that I am beautiful and young and that I give light, air, and energy to the German parliament below. I am loved and admired by millions of eyes, and that makes me very happy indeed. I was born a Princess of Democracy, you see, and to whoever might say that that sounds a bit strange I simply respond: “not at all!” It sounds great in many languages: Prinzessin der Demokratie, Princesse de la Démocratie, Princesa de la Democracia, Principessa della Democrazia…

My beauty is blinding. I recommend you bring a pair of sunglasses – no, really. But not to worry, if you have forgotten yours, you can buy some new ones at Käfer, the restaurant right up here next to me. It’s the best deal around, and the glasses are a necessity! Democratic glasses, princely coffee.

The view up here is breathtaking. You can take in the entire city of Berlin from east to west, from north to south! But that’s not all! From up here you can also explore the northeast, southeast, southwest, northwest…everything! Right at our feet! All the way around! A full 360°!

I am English, you see. My father is the English architect Sir Norman Foster, even if, you’re right, I was born and studied here in Germany. In any event, being the Princess of Democracy is the best job in the world. Ever since I was a little girl I have never dreamed of being anything else. Not a ballerina, not a teacher, not a firewoman. The Princess of Democracy. And I was determined! One day I told my father, “Daddy dear, I would like to become the Princess of Democracy.”

And he, as per his usual, simply answered, “Clara, you are and have been since you were born! However, if you would like to do something useful, go study: know thyself!” In all honesty, I had intended to go to university to get to know people, but, alas, that was not the way it was to be.

He continued, “And as far as people are concerned, don’t you see enough of them already? Try and see who you really are.”

So I decided to have a look, and then another, and continued all the way through the 360 mirrors there in my cone of light, which are distributed across 30 rows of 12 mirrors each. I counted and recounted the 24 plates of glass that cover me directly, and I multiplied those by the 17 floors weighing upon my skeleton, which is itself made up of 24 vertical triangular ribs spanning from my base to my summit and externally reinforced by 17 horizontal beams of steel.

Multiplying 17 by 24 I came up with 408, which means that I am covered by four hundred and eight plates of glass. To be on the safe side, however, I decided to ask a class of young children who were visiting. They fought a bit, of course, and a few insults were bandied about, but eventually they all agreed upon the final number.

The 17 rows concentrically climb one upon the other all the way to the top. My maximum diameter measures 40 meters (131 feet). The empty space between the lower and higher levels was left open in the first three rounds so that I can breathe, and so that you can too. Air also arrives from the 8-meter (26 foot) eye at my summit, which is protected by the finest of transparent nets so that no birds fall in. Yes, that’s right, birds of every kind and species arrive in droves from all over who knows where and they no doubt would fall in out of the curiosity to see the famous 58 square meter (624 square feet) eagle of ionized aluminum which weighs 2.5 tons and which has hung upon steel cables before the glass wall of the plenary chamber since December 17, 1998. Everything is “atwitter” down there, from dawn to dusk –

But is it true that the new bird is a third larger than Ludwig Gies’ old “Fette Henne” (“fat hen”) that hung in Bonn?

It’s true, it’s true.

Is it true that Foster would have liked a bit of a smaller one, but after one hundred and eighty drafts, he settled for the big eagle we see here today because, as everyone said, she was a bit too nervous when she was skinny?

It’s true, it’s true.

Just look at the forbidding look of the eagle at Platz der Luftbrücke at Tempelhof – now that was a true Nazi eagle! Every time the German eagle was just skin and bones an aggressive spirit and expansionistic tendencies seemed to get the upper hand, you know? Really? How do you know that?

I know, I know.

Is it true that she couldn’t make it through any door and they had to bring her inside in three pieces?

It’s true, it’s true.

But doesn’t she resemble the Buddha a little bit?

What? Nonsense!

And yet, this is what I have to listen to all day long, every day, Sunday included. And then they have the nerve to say that birds are on their way to extinction! They’re all here! Once they have finished twittering about the eagle they move on to tweeting about ecology.

At the beginning, however, they were all afraid. The larks sent the crows up to look around and to make sure all the mirrors weren’t a giant trap. Once assured that it was simply an ecological device, however, one fine spring morning there began a bona fide avian symposium on definitively explaining just what the structure meant.

Clearing her throat, a swallow revealed the secret. “Hidden within the glass-plated cone is a heat recovery system which takes up the thermic energy from all the stale air released by the plenary chamber in order to heat the building.”

“Goodness!” responded a tit.

From the southern roof a pigeon answered, “Here there are 300 square meters (3, 229 square feet) of solar panels!”

A blackbird echoed, “And here on the roof of the Paul-Löbe Haus and the Jakob-Kaiser-Haus too!”

The swallow answered, “Well, as I’ve been told, what’s fundamental to the environmental strategy is the central combined heat and power plants of the parliamentary quarter.”

“Cogeneration? Cogeneration?” sputtered a parrot.

At this point, fresh from her studies, a little sparrow took up the discussion, “Well, according to the principal of cogeneration, the heat formed during the production of electricity is used to heat the parliament buildings. Thanks to this technology, the installations can provide 50% of the electricity and 100% of the heat or cold required by the environments.”

A woodpecker hastened to add that the heat which wasn’t used in cogeneration was saved in a type of absorption unit for the production of cold air or stored in summer in the form of hot water in a natural tank situated in a subterranean aquifier at about 300 meters (approximately 984 feet) below the ground that could then be used in the winter.

“Genius!” the blackbird decreed.

“So it is true…they are more intelligent than we are…” a partridge whispered laconically.

“Come on!” exploded an exasperated hooded crow. “They’re just copying us! Like when they said they were the ones who had invented flight!”

“I heard once,” a robin began, “that they went to the desert in order to spy on a camel so that they could understand the secret to its thermoregulation and that then…”

And all of a sudden a great din began with all these supposedly secret stories, and it has not finished since. This permanent assembly comes and goes in flocks every darned day and informs itself and informs its comrades on all the technology and energy saving devices and how the building utilizes clean energy.

They say that they can’t let their guard down for a single minute, that they must continuously pay close attention to the air. They constantly listen to the eagle’s reports from the plenary chamber (which are sent by pigeon) and some days seem to be happy, other days unnerved. These Reichstag birds are like an invisible lobby! But they’re so organized, so informed, and so aware that, to them, the pigeons of Piazza San Marco, the crows of the Tower Bridge, the seagulls of the Sagrada Familia are all just poor imposters…

But where were we? Oh yes, I was telling you about me.

Inside you will find two steel ramps, one in front of the other, rising at a grade of eight degrees and forming a double helix. You go up on one side, and come down on the other: 230 meters (755 feet) of sensational ascent and descent while suspended there within the blue, gray, rose, orange or whatever other color the sky has decided to wear at the moment. No, no, there’s nothing to worry about, your feet are quite safe there on the steel. But, you do seem to be floating in space. Your body is protected by the glass cover while the curls of the helix magically, yet naturally, push you forward with the exhilaration of take-off. Truthfully, I have no idea how it works. The ramps weigh a total of about 800 tons. I haven’t asked any children, but the figure is certain. The material is there but you do not feel it. Being and non-being. What did my father mean by all of this? Who am I? Why am I?

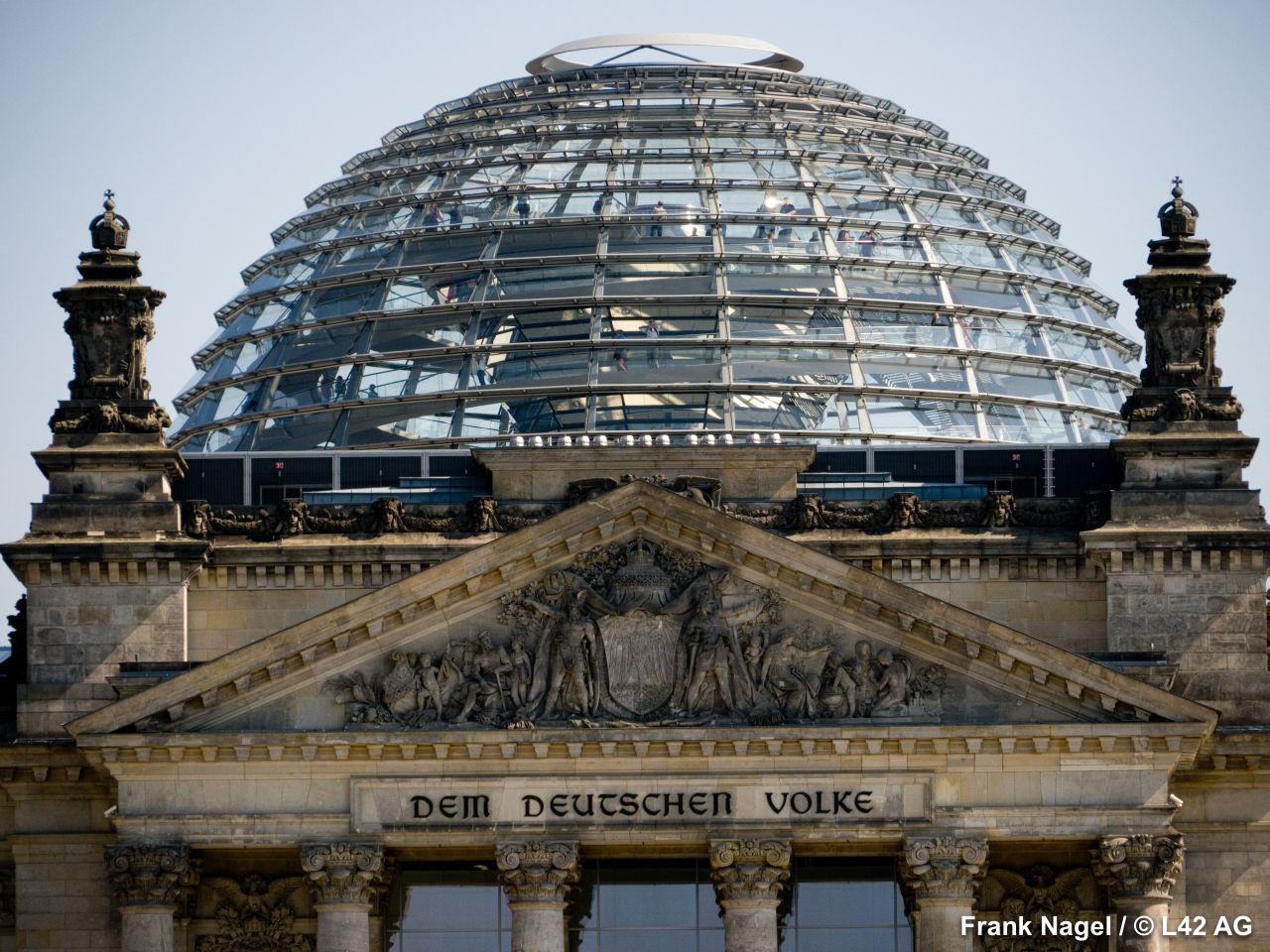

Well, a dome like me rising above the German parliament is not only beautiful, but a symbol of transparency, participation, and the sovereignty of the people who, quite literally, rise above their representatives down below in the plenary chamber who are busy preparing decisions in their name. There is no entrance fee, just a long line if you haven’t booked your visit in advance or at Käfer. You can come any time you like between 8 a.m. and 11 p.m., just like you were at home. Indeed, on the architrave it states that it is your home: DEM DEUTSCHEN VOLKE, in big 60 centimeter (24 inch) letters, visible from afar even by those who are short-sighted, longsighted, or a bit tipsy. Which is to say, there’s no risk of getting the wrong door, of going and knocking at the Kanzleramt next door, for example.

But just what is this German Parliament of which I am the dome? In its own words, it is a parliament directed toward a bright, just, environmentally friendly, democratic, and tolerant future. It is a parliament that respects the artists living and working in its society and considers their feelings and ideas. It is a parliament where the beautiful is to be the symbol of moral good. It is a parliament which has not forgotten the past.

Here next to me is a short exhibit on Germany’s history. And even if we’re talking about the Parliament and not the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art, the history, above all, of German art over the last decades is well represented here.

At the main entrance we have three 3-meter-wide glass panels by Gerhard Richter, which, when placed one on top of the other, have a combined height of 21 meters (close to 70 feet). It is called Black Red Gold and is meant to remind you, naturally, of the German flag. And yet, it is also much, much more. The lightness and the fragility of the glass remind us of the fragility of democracy, no less than does its beauty, luminosity, and transparency…And then, in front of Richter’s panels, are Sigmar Polke’s five brilliant and ironic illuminated boxes collectively known as On the Spot, which accompany the visitor changing perspective as they pass by thanks to a layer of prismatic plastic.

One can feel the substantiality of the materials in the sculpture of Ulrich Rückriem in the south courtyard. And whoever would like to pray or meditate has the mystical, extremely quiet, multi-faith chapel designed by Günther Uecker to seek refuge in: a simple space containing the simplest of altars and a series of minimal panels unattached to the walls, which transmit the idea of the transience of human life.

And what is there to say about the poetic and ethereal Only with wind with time and with sound by Anselm Kiefer? A large-format painting exhibited in one of the reception rooms it seems to tell us that all which seems to us so concrete today is in reality lost in a condition of exile and, broadly speaking, the uncertain and partial experiences of human nature?

In the north entrance hall the US American artist Jenny Holzer has installed a four-sided LED stele displaying the texts of speeches organized into thematic blocks, which were made in the Reichstag and German Bundestag between 1871 and 1999. They can run uninterrupted for almost 20 days. At night you can no longer see the sides so it seems as if the words are holding up the ceiling. Psychedelic!

Hans Haacke’s installation consists of a large type of flowerbed in the north courtyard at the center of which with neon letters in the same manner of the inscription over the main entrance DER BEVÖLKERUNG (To the Population). He asked parliament members to bring bits of earth from their constituencies and installed a webcam so that people could see what was growing, thereby highlighting the responsibility shared by the representatives of the people, the people themselves, and the earth as the origin and end of all.

Herman Glöckner plays with geometric forms as they were actions and sees that they produce light and shadow; Joseph Beuys placed his table with a battery and wires and two balls on the pavement next to the plenary chamber’s exit as if to say “Achtung! Achtung!” Such simple and familiar objects with an extraordinary symbolic and evocative power.

Jens Liebchen photographed the artists during the conception or installation of their works, thus documenting this very new encounter between politics and art. Two completely separate worlds, one might say, and yet, two worlds which are learning to live together, engaged as they are in continuous conversation.

This has to be the most beautiful parliament building in the world! But how do such saintly and luminous domes arise? Is there a recipe, an abracadabra of beauty that could transform all parliamentary buildings in the world into such marvelous creatures? When you see a parliament building that is this perfect inside and out, this clear and clean in its essential lines, you are inclined to think that beauty is an easy thing to accomplish. In reality, what we see is the end result of an extremely long process which itself is the result of an extraordinary amount of work by many people. The construction of our parliament building was as exhausting as the construction of our parliamentary system. And when the former was murdered, it was also burned, and then devastated by bombs…and yet, in the end, after a lot of effort and decade-long discussions, it arose once again from out of its ashes to become what you see today. Ours is a painful history, but you already knew that.

So, above all, just what is parliamentarianism? This is an extremely important question. Indeed, what need would there be for a parliament without a system of parliamentarianism?

Wilhelm II, the reluctant commissioner of this building, believed, for example, that parliamentarianism was something for women and for the French. Good Germans, good men, on the other hand, had no time for such nonsense. Leaving Hitler’s arguments in Mein Kampf aside (which was published in 1925), what is undeniable is the fact that a certain intolerance toward parliamentary principles was long much more diffuse in our society than one can imagine today. Prussian militarism and authoritarianism first, and National Socialism and communism thereafter, were anything but pervaded by a democratic and parliamentarian spirit. And yet, in spite of such aversions, the Parliament was constructed. How exhausting!

Work began June 9, 1884, and immediately proved difficult. From the very beginning, there were problems with the foundation. The sandy ground of Berlin didn’t and doesn’t support much at all. Then there were the strikes (and you mustn’t forget that productivity was not what it is today, materials were still primarily brought by draft horses!). If I were to tell you that it took eight years just to realize the rough stonework, from 1884 to 1891, two more years than expected, maybe the image wouldn’t be as vivid as if I told you that throughout all four seasons and the bad weather of 1884, 1885, 1886, 1887, 1888, 1889, 1890, and then 1891, crowds of construction workers took turns at the immense work site. Sadly, some of them died quite young after falling off the scaffolding like Gaetano Negri, Otto Keller, Ernst Giersch…

Are you familiar with Bertolt Brecht’s poem Questions from a Worker Who Reads? You know, the one that goes “Who built Thebes of the seven gates? / In the books you will find the name of kings. / Did the kings haul up the lumps of rock? / And Babylon, many times demolished. / Who raised it up so many times?” (trans. Michael Hamburger). Well, just try and think of the huge number of construction workers here…

In any event, Paul Wallot was the name of the Reichstag’s first architect and he had Huguenot roots. His contemporaries described him as a man gifted with extraordinary intelligence, energy, a sense of humor, and the ability to resist adversity. And it was this latter talent, in particular, that proved essential for being able to carry out the hard work of being in the service of the Kaiser. A certain dialectical tension between the commissioner of a project and the architect is understandable and the history of art is also the history of many bouts of gastritis, depression, and fits of anger. Here, however, we’re talking about something a bit more serious – let’s call it a bullet-less duel – between Wallot and the Emperor Wilhelm II.

Wilhelm I was still Emperor when works began in 1884, and he grudgingly followed construction through 1888, the year of his death. After the brief interlude of his already gravely ill successor, Friedrich III, Wilhelm II came to power and inherited from Wilhelm I his role of protestor and shone with all of his obstinate, conservative splendor. The sovereign was preoccupied with maintaining control over an absolute state and expanding the empire’s power while taking shelter culturally and morally within traditional values and tastes. On the other hand, the Kaisers were used to deciding everything and their subjects to a large degree were used to obeying everything. But within society in general, and here within our story with Wallot in particular, something new was taking place. The role of the architect – as Paul Wallot understood it, for example – was on the one hand practical, in the sense that he was the point of reference for all of the workers and their day to day problems, and, on the other, directed toward dreams, the ideal, the sun, and paradise (as he himself liked to say). He was so inspired that he didn’t perceive any restrictions at all. And among his dreams was that of realizing a dome that would not be made of stone, but of modern materials. It would be made of iron and glass and would be an expression of the synthesis of all of the various arts.

The Kaiser, however, did not much appreciate Wallot’s choice of materials. And more than anything, he seemed to be offended by the fact that the dome of the Reichstag would be 75 meters (246 feet) tall, in other words, five meters taller than his castle and six meters taller than the Siegessäule (the Victory Column). And so, between 1891 and 1893, when the dome was being constructed and the interiors were being set up, things began to get a bit heated.

In April of 1893 Wilhlem II was in Rome when he exclaimed that he found the Reichstag and its dome to be the “sum total of a lack of taste” in so doing adding to his previous statement that it “seemed to be a house for monkeys.” The first to show their solidarity with Wallot were the Roman artists and then it was artists throughout the world. In addition, diplomats were worried about the potential damage provoked by the Emperor’s words.

Wallot was made an honorary member of the most varied associations of architects and designers yet felt it was in any event healthier to leave Berlin in October 1894 in order to go and work in Dresden.

The Reichstag was inaugurated December 5, 1894, with a military parade, but the sovereign expressed not a single word of acknowledgment or thanks to the architect. The President of the Parliament, Albert von Levetzow, invited the deputies to come celebrate in the restaurant, asking the stenographers however to leave it off the record. Between one round of drinks and another, the party continued on well through the night and into the following morning. The evening of December 7, however, was reserved for the workers: 600 engineers, architects, painters, and sculptors.

Wallot’s proposal to dedicate the building to the German people with an inscription upon the front between the six gigantic columns and the tympanum was rejected by the sovereign, the press, certain intellectuals, and public opinion. The newspaper the General Anzeiger from Frankfurt on Main had commented on January 27 and 31, 1895, that one could use a sign on a commercial establishment for private purposes like informing the clients about what kind of store it was but certainly not for Parliament! (It was only to be in 1916 that Wilhlem II capitulated on the question as to the dedication, hoping thereby to boost the people’s morale in that inauspicious year of the war, which instead of being brief and victorious, was taking a turn for the worst).

But what happened within Parliament after the inauguration celebration? 1895 was the beginning of the painting work of Gustav Schönleber and Eugen Bracht. Angelo Jank came thereafter with his celebrated historical paintings. Instead of choosing a theme of a parliamentarian nature, however, he thought of depicting the Battle of Sédan – practically speaking, a metaphorical slap in France’s face. He was criticized for both his choice and for its realization. Was it possible that the Germans just couldn’t manage to free themselves from their anti-French stance? It’s possible. It was 1908. The assembly hall was completely redone in wood in order to improve its acoustics. At that time the parliamentarians’ heads were loomed over by a heavy bronze lamp that measured 8 meters in diameter.

Having by that point finished with the Reichstag, this vaguely Renaissance-Palladian-proto-Baroque stone monument topped by a modern and rectangular dome of green glass and steel, it was now time to construct the square.

The new construction, however, was simply swallowed up in that grassland of 11 hectares (27 acres) known as the Königsplatz. Any hopes of standing out in that immense bit of land was, at best, slight. Wallot therefore thought of subdividing the entire outer appearance by planting trees. And that’s what they did. Naturally, it wasn’t a move that complemented the building like Bernini’s columns do around Saint Peter’s, but at least it was something.

When Bismarck died in 1898, it was immediately decided that a statue to him should be erected in front of the Parliament. This decision was followed by a two-year long debate on the materials to be used, the position that his body should take, whether he should appear in uniform or not, and whether his hat should rest upon his head or be held in his hand…In the end, ironically enough, Reinhold Bagas would be the one to design it.

That huge space before the Reichstag which, despite the corpulent statue of Bismarck and all the trees, still remained voluminous, however, was immediately to become the backdrop once again to history. And history, as per its usual, greedily stole the whole scene.

On August 2, 1914, the entire square was full of people enthusiastically celebrating Germany’s entrance into the war. Just two years later, at Christmas in 1916, the people were to be consoled for their losses with the gift of the dedication, “Dem Deutschen Volke.” On October 28, 1918, in the very same square once again people railed against both the bourgeoisie and liberals, guilty as they were in the peoples’ eyes of every form of evil. A few weeks later, at around two o’clock in the afternoon on November 9, 1918, two social democrats who had voted in favor of the war (but who could not stand each other) – chairman of the SPD Friedrich Ebert and deputy chairman Philipp Scheidemann – were sat at two different tables in the restaurant of the Reichstag eating their potato soups. The crowd of demonstrators outside, however, continued to howl, so someone from the Parliament was needed to calm them down. Seeing that Ebert did not want to go outside, Scheidemann stuck his head out of a window and proclaimed “Workers and soldiers! These last four years of war were horrible, gruesome the sacrifices the people had to make in property and blood; the unfortunate war is over. […] The Kaiser has abdicated. He and his friends have disappeared. […] Prince Max von Baden has handed over the office of Reich chancellor to representative Ebert. Our friend will form a new government consisting of workers of all socialist parties. […] The old and rotten monarchy has collapsed. The new may live. Long live the German Republic!” (trans. A Ganse).

In the Parliament Ebert thundered against his colleague’s decision to proclaim the Republic. He believed that Germany’s fate should have been decided by Constituent Assembly and had previously also openly hoped to save the monarchy. The Kaiser was forced to finally abdicate his role as Emperor and King of Prussia even if he only did so on November 28. Friedrich Ebert was later elected provisional president on February 11, 1919, in Weimar while his colleague Scheidemann was elected Chancellor.

For the following three months the Reichstag was occupied by soldiers. Anything that was of value disappeared: the silk curtains, the leather chairs which were valued at about 2,500 marks a piece, the candelabra…that which was left behind was dirty and ruined. With April came the great spring cleaning and the rooms were disinfected, but the times had unequivocally changed. Tensions ran high. Riots and violence were constant and a constant source of concern.

On June 24, 1922, there was a state funeral for the assassinated ex-minister Walter Rathenau. The overture to Beethoven’s “Coriolanus” was truly the right music at the right time: a dramatic crescendo, an attempt at reestablishing harmony, a plea for delivery from blind violence, and finally the relentless chase toward a terrible destiny.

On February 28, 1925, Friedrich Ebert died and on April 26 the monarchist General Paul von Hindenburg was elected president. It’s curious that both of the first two presidents of the Weimar Republic were monarchists and yet remained loyal to their republican oaths, isn’t it?

Between bombs and hymns to intolerance, somehow we arrived at the elections of July 31, 1932, which would see the Nationalist Socialist party become the majority with 230 seats versus the socialists’ 133, the communists’ 89, and the moderates’ 85. On December 6, 1932, Hermann Göring was elected president of the Parliament. Violence and clashes followed.

On February 1, 1933, the Parliament was dissolved. On the evening of February 27, between nine o’clock and ten-thirty, the Reichstag went up in flames. A young Dutch anarchist, Marinus van der Lubbe, was arrested, charged with arson, and executed in December of the same year after a show-trial intended to be a political trial of communism. Many suspicious circumstances point to the fact that, in reality, the act had been committed by the National Socialists themselves in their plan for a progressive creation of a climate of terror. Not all of the Reichstag burned, however, “only” the plenary chamber and a few adjoining rooms. The library, the conservatory, the boardroom, and the stenographer’s hall remained usable.

As we know, Hitler came to power January 30, 1934. But how did the Führer use the Reichstag? He had the part which had been burned reconstructed, he had it stripped of books and ornamentation, had a bunker built, had the bronze of the remaining lamps sent to Hamburg to be smelted, had the statue of Bismarck transferred to the “Grosse Stern” in the Tiergarten, and had the building incorporated into Albert Speer’s designs for the construction of what was to be the new Hauptstadt (capital) “Germania.” Among other things, he paid homage to the citizens of the Reich with two exhibits: “Bolshevism without a Mask”, which hung between November 6 and December 19, 1937; and “The Eternal Jew”, which hung between November 12, 1938, and January 14, 1939.

And even if the Reichstag was not really used by the National Socialists as a Parliament (which instead met in the adjacent Kroll-Oper), and even if the most horrible decisions were to be made in other places, the Allies found the monument particularly odious and therefore attempted to destroy it with all their might.

And succeeded.

In the last months of the war when Berlin was being heavily bombed, an attempt was made to save the books by bringing a large number of them to the Schloss Bellevue (Bellevue Palace) – which, however, was struck in February 1945 – and another part to a warehouse in the Weinmeisterstraße, which was itself destroyed in an air raid right at the end of the war on May 2, 1945. In the latter space alone they counted 400,000 burned books while the remaining 8,000 books that had escaped the flames were sold throughout the world by the GDR’s used booksellers.

The war finished for the Reichstag on April 29 or 30, 1945 – the dating of the photograph is uncertain – when two Soviet soldiers installed the red flag on the roof. And that is where it remained until May 20 when it was removed in a military ceremony and sent to the Military Museum of Moscow. And that was the moment the so-called “hour zero” began, not only for the Reichstag, but for the entire country. Purgatorial souls wandered in a daze throughout the square, the difference being that souls in purgatory don’t feel the pangs of hunger, don’t traffic in black-market cigarettes, and, in some way or other, believe in something.

In 1945 a good number of the 2,300,000 inhabitants of Berlin moved throughout the square daily either because of the black market, the raising of potatoes, or just to hear the latest news. Existential problems ceded to ones of necessity, however, and the destiny of the Reichstag in those months really seemed to belong to the former. At the beginning of 1947 there was even talk of tearing it down completely, but then Berlin was divided into its infamous four sections.

The charismatic Ernst Reuter became the mayor of the Allied Sector on April 17, 1947, and on March 31, 1948, Königsplatz became the Platz der Republik. On September 9 of that same year 350,000 people came here to protest against the Soviet imposed blockade and the subdivision of the city. It was here that Reuter held his now famous speech: “People of the world…look upon this city and see that you should not and cannot abandon this city and this people!”

On May 1, 1949, Jakob Kaiser, anti-Nazi and cofounder of the new party of the CDU (Christian Democratic Union), spoke to the people gathered in the square after the decision had been made to rebuild the Reichstag. Thanks to a proposal of the SPD on September 30, Berlin was to be considered the democratic outpost of Germany and that at some point in the future it would once again be the capital. And so from the very beginning Bonn was only considered a temporary solution.

When the government of East Berlin decided to blow up the Schloss, people rushed to establish the fact that the Reichstag belonged to the state and not to the city of Berlin and thus every decision as to its future should be made by a central committee (and in Bonn as it turns out). Hence, it was saved.

On May 27 the Kroll-Oper – the former seat of the Nazi Parliament – was torn down.

In August 1952 the great spy film “Die Spur führt nach Berlin” (“Adventure in Berlin”) was directed here. The director was given permission only to film on the north side, however, for a report had established that the dome was unstable and therefore absolutely had to be demolished.

After a lot of preparation, this was planned for October 23, 1954. The East German police were also alerted, as they were just a few feet away on other side of the border. The work to be conducted – at 70 meters above the ground – was not easy and, as you know, October in Berlin is cold and humid. And it was thanks to this humidity that that day it was impossible to get the fire going as necessary and the cold then immediately resolidified the metal that was supposed to have liquefied. Thus, a second attempt was necessary, and this took place on November 22.

Once again on May 1, this time in 1952, for the first time since becoming President of the Federal Republic of Germany, Theodor Heuss announced his intention of having the Reichstag rebuilt: “We all shall live and work until this house returns to being the country and the forge of the future of Germany.” The Reichstag was therefore considered a symbol of the reconstruction of Germany. Nevertheless, the exact role the space was to assume remained unclear. Should it become a memorial or a new Parliament building?

On October 26, 1955, there was a debate surrounding the SPD’s proposal of a 60,000 mark competition for the reconstruction of the Reichstag. Willy Brandt was extremely in favor of it. 2,500,000 German marks were then approved for the restabilization of the building and for the removal of rubble. The first 500,000 marks were to be taken from the 1956 budget 1956 the remaining 2,000,000 from the following year’s.

In 1958 the façade was renovated by removing all of its ornamentation. There were no major criticisms. Some said that Wallot would not have wanted it that way, but there was a predominantly positive mood as far as these signs of reconstruction were concerned.

The competition for the reconstruction of the Reichstag, as a symbol of Parliament and the strength of democracy, was officially announced on May 12, 1960. That was the spirit of the times: the symbolic took precedence over both style and decoration.

In his extremely thorough volume Der Reichstag, Parlament – Denkmal – Symbol (The Reichstag, Parliament – Memorial – Symbol) Michael S. Cullen reports on how difficult it is to trace sources related to this second remaking of the Parliament. Though much has been written on Wallot, there is a lot of silence surrounding the reserved architect Paul Baumgarten.

I should mention, however, that they were rebuilding the Parliament when the times did not appear particularly propitious for the reunification of Berlin. And they did so, if not exactly in secret, then, we could say, with a certain amount of discretion. The German Democratic Republic, as you might imagine, was completely against the project.

On December 31, 1969, when the plenary chamber was unveiled to the public (in full awareness of the fact that it would not be used), a strange feeling of emptiness, of expectation swept through the building.

On the centenary of the first parliamentarian assembly on March 21, 1971, the exhibit “Fragen an die Deutsche Geschichte, Wege – Irrwege – Umwege” (“Questions of German History – Paths – Wrong Ways – Detours”) was opened to the public. Prior to its transfer in 1994 to the German Cathedral on the Gendarmenmarkt (where you can still see it today), it had welcomed 10 million visitors.

Waiting is a strange sort of limbo. But the Reichstag, the Penelope of the post-war, kept her nerves and knew how to be patient. Twenty years of patience in fact. And in the meantime, she wove throughout the day and unloosened her weave again at night. But for the most part she wove.

Between June 27 and July 7, 1995, Reichstag-Penelope displayed her cloth of polypropylene and aluminum to all in order to celebrate the return of her “Bundestag-Ulysses” to “Ithaca-Berlin” within a great atmosphere of joy and peace – almost like a kind of German Woodstock with 5 million visitors.

But what had they been doing all those twenty years? They were attempting democracy, let’s put it that way, and in a certain sense it was a true path of initiation in no way dissimilar to the labyrinthine travels of Odysseus: full of exhausting debates and discussions and day after day intent on restoring the idea of Germany. Yes, because, as it was the Parliament and the place of democracy par excellence, the decisions facing them took on entirely new symbolic value not only for the Germans, but the entire world.

As the entire world was watching Berlin with particular attention, at the same time as preparations were underway for the new parliament in 1971, Michael S. Cullen (the great biographer of the Reichstag I mentioned just a moment ago) came up with an idea of presenting a sensational artistic Aktion that would involve the whole building. He contacted the artist couple Christo and Jean-Claude – who expressed their vision of the world by wrapping up objects and various pieces of art – and asked them if they would be interested in wrapping up the Reichstag. The artists were not opposed, but the project was without a doubt ambitious to say the least and it required a large consensus. In 1976 the President of the Bundestag, Annemarie Renger, voted in favor of the project, but the following year the President of the Parliament and future President of the Federal Republic, Karl Carsten, blocked it. However, the mayor of Berlin, Dietrich Stobbe, immediately put it back on the table for discussion. Nevertheless, it wouldn’t be until 1982 before it was discussed again favorably when Reiner Barzel, President of the Bundestag, and then Richard von Weiszäcker, first mayor of Berlin and then President of the Federal Republic, brought it forward once again.

In 1985 Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s wrapping of the Pont-Neuf in Paris won international acclaim. After that success, the public seemed ready for more and, right after the reunification of Germany and right before giving the final go for reconstruction, the President of the Parliament, Rita Süßmuth, contacted the artists on February 9, 1992. In February 1994 a heated discussion took place in Parliament and the CSU, the CDU, and the Liberals expressed their displeasure with the project. However, after a series of convincing, optimistic speeches, the wrapping was again underway. “We’re ready!” the artists declared. “Let’s move on to the work one month before official reconstruction begins!”

But, once again they had to wait. And then on June 27, 1995, they were finally able to stretch the 100,000 square meter veil across the monument and keep it there until July 7. It had only taken twenty-four years and a river of stories, but there it was. In the end, 96 out of every 100 Germans saw the image of the Reichstag under wraps and 5 million visitors came to see it and could say with pride that they were among them!

Beyond the history of the wrapping of the Reichstag, however, those years also saw the reunification of Germany and on the Platz der Republik they celebrated nonstop.

On October 4, 1990, the new Bundestag and the new parliamentary assembly met for the first time in fifty-seven years. For the first time, that is, since December 9, 1932, in the Reichstag. It is impossible to describe the happiness of those months.

When Willy Brandt’s funeral took place on October 16, 1992, along with the feeling of loss, in the plenary hall there was also a feeling of completion, of a course having been run, and of an openness toward the future.

Well, you may be wondering what the new Reichstag here below my feet looks like? It is a principally functional structure made of modern materials in order to respond to the needs of a modern assembly and to provide a great aesthetic impact. It is an efficient beauty, you could say, nourished by its past in order to better understand its future.

As a visitor you enter through the principal entrance on the western side, while the deputies mainly come in from the east, which is more easily accessible by automobile.

You, the people, can ascend the stairs and arrive at the mezzanine by the subtle steel bridges that provide a contrast to the imposing air of the vaults in the masonry. My father had all the panels removed which Baumgarten had had installed. In the 1960s they had wanted to forget the war, but by now they had found the strength to uncover the dozens and dozens of examples of Cyrillic graffiti the victorious Russian soldiers had left in the spring of 1945 along with all the bullet holes.

From the mezzanine, distinguished by a dark green door, you, the people, can spy on the necks of your representatives down in the plenary chamber through the glass. Their armchairs are arranged in a semi-circle – a special form, neither open nor closed, different from other famous parliaments – which looks onto the rows of chairs reserved for the members of the government, the Bundesrat, the presidency, and the parliamentary commission for the armed forces. Behind the deputies’ chairs are the visitor and press galleries. The heart of German democracy before you measures 1,200 square meters (approximately 12,900 square feet) and has 24 square-meter-high (258 square foot) gray walls, gray soundproof panels, twelve subtle gray columns topped by lights, the gray Presidium, the gray stenographers’ bench, and a gray carpet which causes the chairs’ extremely particular blue tending toward violet (so-called “Reichstag” blue) to stand out all the more. Underneath the chairs is a fire extinguishing system and beneath the carpet – can you believe it? – you won’t find a normal pavement but a steel structure mounted by a perforated metal mesh which helps to bring in fresh air from outside and draw the stale air out through an air extraction plant located in the center of the cone-shaped light sculpture which then exits through the opening I have above my head. Even the passage of air moves from bottom to top! When you say total democracy…

At the level of the plenary chamber you can find the lobbies, the halls, the bistrot, the café, the restaurant, the chapel for prayer and meditation, and the library. Here, as I mentioned at the beginning, the doors are all blue.

On the next level, behind the vivacious burgundy door, you’ll find the Council of Elders Room, the protocol chamber, and the offices and reception rooms used by the President of the Bundestag. Here everything is a bit more spacious and the pace a bit slower while the wall of glass allows you once again to look down on the plenary chamber if in the mood.

On the third floor you’ll find four towers, each dedicated to a different parliamentary group.

And finally we have courtyards and terraces, but the spaces aren’t enough for the well-designed machine that is our democracy and so next door in the Paul-Löbe Haus you will find 510 rooms for the deputies, 450 offices for the commission secretaries, and two-level halls, contained in eight rotunda and reserved for the commissions. The nearby Marie-Elisabeth-Lüders Haus, on the other hand, is the reservoir of all of Parliament’s knowledge: it holds the archive, library, press documentation center, and the departments of various scientific services, but also a contemporary art hall which hosts exhibits of a political nature. The Jakob-Kaiser-Haus in its turn houses offices, television studios, a press office, a stenographers’ hall, and conference rooms…

And now comes a difficult moment for me, that is, Clara. When my father, Sir Norman Foster (in case you’ve forgotten his name), invited me to get to know myself I imagined it would be enough to look into the mirrors in the cone of light to see who I was. I began to study my past history out of personal curiosity, but no one had ever told me about all of those things closer to the time of my birth. Out of modesty perhaps, or in order not to upset me with existential aggravation once I reached puberty.

In 1992 and 1993 there were important debates as to the usefulness of reconstructing the cupola. In the line-up of those in favor you could find the CDU and the CSU, both of whom wanted for aesthetic reasons to reinstate the old model exactly, but didn’t want the restoration to have any political significance. Then there were others who didn’t want a cupola and even some who didn’t want the Reichstag itself at all.

In February 1994 my father and his huge firm of dozens and dozens of associate architects presented a project which was against the historical reconstruction of the dome due to its lack of functionality: too much space and energy would be wasted. Instead, they proposed a light, transparent roof, which was to rest on thin, tapering steel supports as well as the first plans for the ingenious cone of light and energy.

“Sheer madness,” people said, “nothing like that has ever been seen on any parliament building in the world!”

And so my father continued to present different kinds of domes only in order to demonstrate their impossibility: one was too heavy, another would interfere with the use of the existing plans, another still would block the light…He seemed to be certain about only one thing at that time: no dome. He believed that you had to look to the future rather than exhume the past.

Together with his party and with the CDU Oscar Schneider, the CSU’s Minister of Public Works, continued, however, to insist on a dome. On June 28 my father was awarded the contract of reconstruction, and he accepted the hypothesis of a modern alternative.

My father said “Yes, I do,” thereby recognizing the needs of the collective. And yet he continued to speak about his cone. On June 30 there was a stormy meeting in which he was asked once again to abandon his idea of a cone and to concentrate instead on a dome.

My father relented, although he still had no idea about any sort of dome. Oscar Schneider felt relieved, and the Bundestag thought it had reached an agreement but no one had really gotten what they wanted. Is this democracy? The journalists went wild.

My father, for his part, took it all in stride. When asked in an interview “And if the Bundestag changes its mind again?” he simply responded “I wouldn’t know, we might all be dead tomorrow. The world in any case continues to turn.”

Schneider did not run again, and the dome’s supporters lost support. In February 1995 my first ultrasound was presented to the world. It looked like a decapitated ice-cream cone, that is, a parabolic form with an open summit like a chimney…inside two ramps, one to go up and one to come back down and in the center, in the form of a funnel, the famous sculptor of light with its 360 mirrors that move to capture the light and reflect it down into the plenary chamber, moved and modulated by a computer system which reveals the excess exposure to the sun and activates the mechanized sunshade…so as not to scald the deputies, you see! And, again, all ecologically sustainable!

A hostile silence and skepticism on the one hand and the voice of Santiago Calatrava on the other who maintained that my father had been a little too inspired by his own proposal.

In March there were serious threats of terminating the whole thing.

In April, however, the by-all-accounts difficult pregnancy continued.

On May 8 the Council of Elders approved the proposal. The supporters of the dome felt like they had been cheated. The papers, public opinion, the Gesellschaft Historisches Berlin all looked at my ultrasound and shook their heads. They said that I looked like a soap bubble, a beehive, and even an English egg and that I didn’t have any European resemblance whatsoever.

The CDU and the CSU who in the 1980s had showed no interest at all in architecture discovered a new vocation and, with the enthusiasm of the newly converted, did not hold back with their criticism, a bit in the style of Wilhelm II one could say, but with the difference that for the conservatives of today, Wallot’s then innovative dome is of a classical beauty and not the “sum of bad taste” as Wilhelm II used to say.

If the Kaiser had only heard them!

My ultrasounds were placed in the papers next to pictures of other monuments to show how I didn’t look like anyone else. Noted intellectuals wanted Wallot’s dome back at any cost and for the Reichstag to remain under wraps forever. A real movement of the faithful gathered around the idea of Wallot’s dome to proselytize. My father’s firm didn’t respond but simply continued to work. They gutted Baumgarten’s work, enlarged the spaces in order to give them light and air, and showed that the project was both ecologically as well as economically sound.

We’re at the end of 1995 now, and I was still being referred to as the English egg. Can you believe that?

In the spring of 1996 there was the last great press campaign aimed at stopping me from being born. Fortunately for me, however, the labor pains began to increase and after a few contractions, with a birth that was for the most part natural, between the autumn of 1996 and the summer of 1998 I finally saw the light of day! And what a light it was! All and sundry gathered around my crib, and no one had anything nasty to say anymore, simply “How odd she is!”

My father smiled and proudly declared, “Time will decide what shall become of her!” And his visionary’s third eye was delighted at the thought that time would no doubt kiss him on the forehead. He knew that the difficulties surrounding my birth would soon be forgotten and that newborns like me would find me not only normal, but pretty and the older ones would enthusiastically agree while adding, beautiful!

He knew that beauty is truly in the eyes of the beholder.

Translated by Alexander Booth